Learning for Innovation

How does your organisation know when it needs an innovative response to a problem? How does it learn what the problems are? How does it learn for innovation? We are seeking your input on our ‘alpha’ version of a study on identifying problems and learning for innovation in the public sector.

Public sector organisations are dealing with large and varied changes in their operating environment. Many traditional practices are no longer delivering the results that are expected or needed. There are pressures to perform, to meet the changing expectations of government and build trust that government can meet the needs of citizens. There is a need to lift productivity and effectiveness, and to work with citizens in new, and more inclusive ways.

In short, public sector organisations around the world need to innovate.

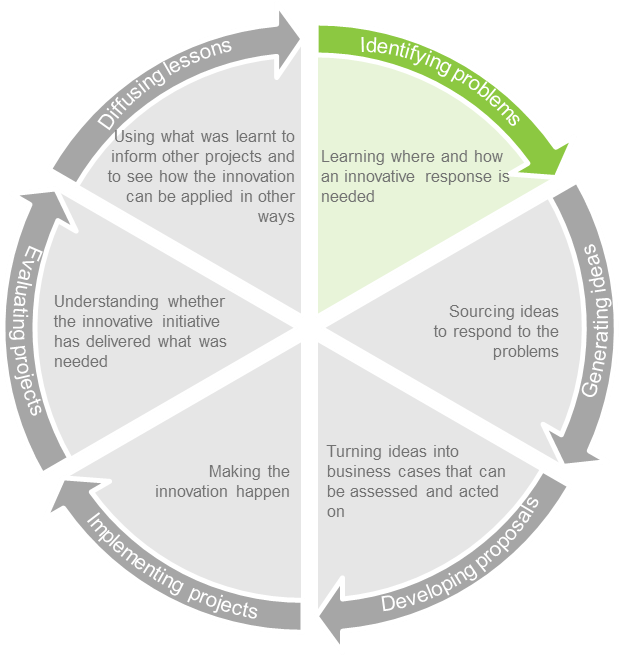

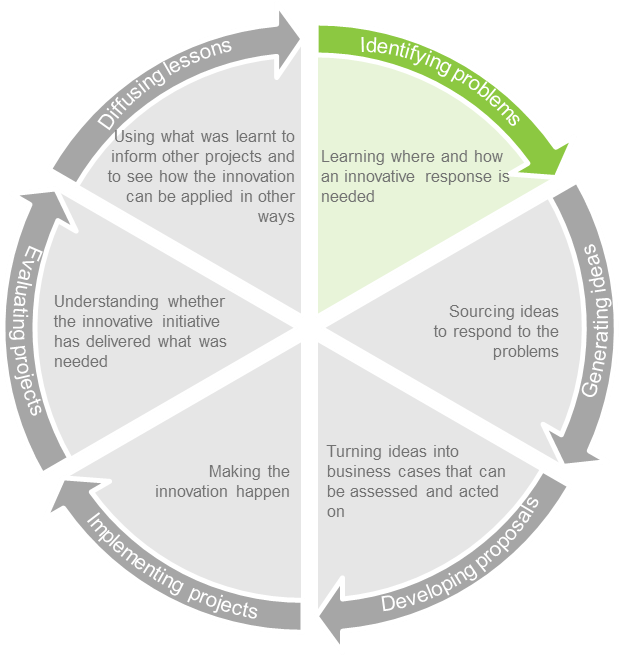

What’s more they need to innovate in a systematic fashion. E.g. organisations need to be able to have a repeatable process that they can use to come up with new ways of responding to problems. While innovation is unpredictable, an act of engaging with the unknown, it is still very much a process, one that we refer to as the Innovation Lifecycle.

And the beginning of that process is to know what the problems are where innovation is needed. If the reason for innovation is not clear, then the inevitable hurdles faced in introducing a new way of thinking or doing things will be much harder, and the other stages of the process much trickier than they need to be. E.g. if you are not clear on the problem you are solving, then assessing which new ideas will be useful will be hard, and effort could easily be wasted on exploring ideas that will not thrive.

How then do organisations identify the problems? Basically – through learning. Through learning what is not working, what might be possible, or what might be coming.

Learning is also a fundamental part of the overall innovation process. Innovation without learning is luck, and governments cannot rely on luck or chance to answer citizen expectations.

Of course organisations have always had to learn (and the public sector has a long history of innovating) but we suggest that there are two characteristics that mean that particular attention needs to be given to learning for innovation.

- The first of these is that learning things that are already well understood is much easier than learning completely new things. Innovation is an uncertain and exploratory process – and learning for innovation involves different considerations than other types of learning

- The second is that public sector organisations are operating in a world where there is a constant stream of new information, and which makes the scale and scope of learning needed very different from the world in which public services evolved.

We suggest that these things mean that we all need to better understand the nature of learning for innovation, the enabling factors for effective learning, the channels by which organisations and people learn, and the tools that can assist.

Thus as part of our Horizon 2020 project on the innovation lifecycle we have produced a study on identifying problems and learning for innovation. We hope this will help organisations and public servants when looking at their innovation processes and considering how they can best identify the problems that need an innovative response.

In the spirit of learning, and safe in the knowledge others will definitely know things that I and the rest of team here at the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation do not, we are releasing this first draft of the study as an ‘alpha’ product.

It is not intended as a ‘working paper’ or a draft. It is, rather, a study containing a set of findings, suggestions and arguments that we want to rigorously test with others. This is a big topic and definitely one that can benefit from multiple perspectives. We are hoping to tap into the wisdom of others, of those who have applied innovative processes in governments around the world, and to hold this work up to questioning, to testing, to experimentation.

As an alpha version, this report is definitely not perfect. That does not mean that a lot of effort has not gone into it or that we are expecting others to do our work for us. Rather, it is done with the knowledge that this will not be a good study unless it is useful for the people it is written for – public servants and their organisations that are trying to do things differently in order to get better outcomes for citizens. And that means we need to learn from you and others, and build in any insights that are shared with us before we lock in our thinking on this topic.

In that vein, we are have published the study on a hackpad, a collaborative site for editing, so that anyone who has comments, suggestions or changes can make them directly into the text of our alpha study (you should be able to edit directly from below as well). A copy has also been provided – Alpha Version of Innovation Lifecycle Study 1 .

We will then work to incorporate the feedback as possible, and release a ‘beta’ version. (A more definitive version will be released once the other studies of the innovation lifecycle are completed). This work will support the development of a practical innovation toolkit that we hope will be used by public servants as they introduce new ways of doing things.

Of course you are also welcome to email us or you can join in on our discussion groups, either on the OPSI Platform or in our LinkedIn Group, and contribute your thoughts there. A copy of the study is also provided as a pdf [link] for those who wish to read it in another format.

This is an experiment for us – so feel free to let us know your thoughts on this process and whether there might be better ways for us to do this in future. We’re very keen to learn!

If you would like to be kept informed about this or our other projects on public sector innovation, then you can sign up to our mailing list or follow us on Twitter.