Innovation facets part 5: Adaptive innovation

In the last post in our innovation facets series, we looked at mission-oriented innovation. In this post, we explore the adaptive innovation facet – what it is, what role it plays, how to support it, and the key considerations.

This post is us at OPSI “showing our work”, as this is still very much thinking that is evolving. Your feedback will help us in distilling the key messages, to ensure practical guidance for public servants everywhere.

Adapt: “Make (something) suitable for a new use or purpose | modify; become adjusted to new conditions”[1]

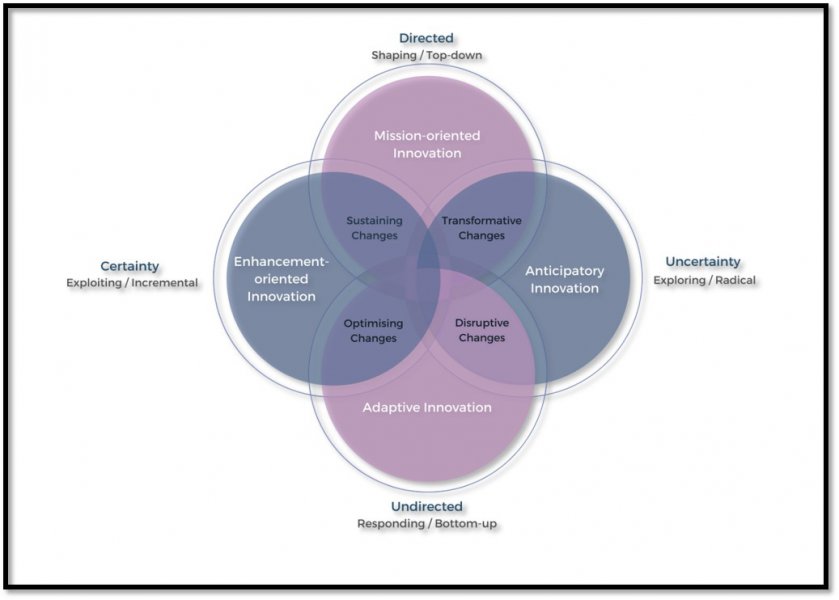

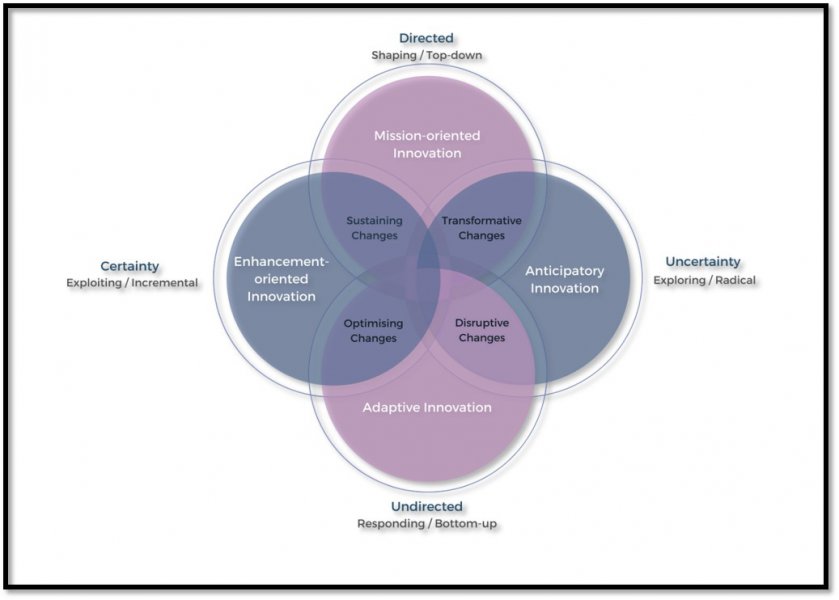

As we noted in the first post in the series, for adaptive innovation:

- the purpose to innovate may be the discovery process itself, driven by new knowledge or the changing environment. When the environment changes, perhaps because of the introduction of innovation by others (e.g. a new technology, business model, or new practices), it can be necessary to respond in kind with innovation that helps adapt to the change or put forward something just because it has become possible (i.e. entrepreneurial discovery).

- it can range from the incremental to the more radical. However the more radical the adaptive innovation is, the more likely that a public sector organisation will either endorse it from a leadership level or seek to suppress it or force it outside of the organisation.

- it is illustrated by the example of how many government organisations have engaged with social media, where they initially started with bottom-up initiatives, and changed some of how they interact with citizens. Much of this innovation has been driven by people and organisations trying to react to a changed operating environment that meant that traditional channels sometimes were reduced in effectiveness, and citizen expectations about what was appropriate, needed and possible changed as social media introduced new ways of interacting. It can be driven by citizens themselves and only later on taken over or integrated into public policies.

- it can be extremely valuable in matching external change to internal practices and usually it cannot be directed top down, because people’s developing needs cannot be prescribed. As such, adaptive innovation will generally be driven from the bottom-up, as those closest to citizens and services will often be the ones who see the need for change and react accordingly.

My colleague Piret Tõnurist gives a quick overview of adaptive innovation:

A perspective from the field – General Services Administration

When the pace of change outside of government is much more rapid than the pace of change inside of government, “pressure relief valves” can be needed to enable more adaptive innovation to occur. A team in the General Services Administration of the United States Government sensed this need and developed a financial and bureaucratic signalling tool to enable safe-to-fail autonomous experiments with new technologies, many of which were already mainstream outside of government.

They developed a program called ‘10x’, an incremental investment fund available to enterprising teams inside the government. It is part innovation lab, part venture capital fund, and part incubator. The team sources and supports internal products and services intended to significantly improve how the US government uses technology for the public good. The team focuses on finding and supporting projects that normal bureaucratic processes cannot: high-impact ideas from federal civil servants on the front lines of the organisation, who often have the best view of the pain points people have with the government service experience as well as what needs to get done. These civil servants often have the least access to the resources that would enable them to actually do something about the pain points. The incremental investment model allows them to do early experimentation with their ideas. The ones that prove their merit become eligible for the next round of funding. The rest do not advance but provide a source of valuable learning about the organisation.

The program was launched in 2017 with 13.8 million dollars of funding and has supported projects include the U.S. Web Design System, the Federalist publishing system, and the TTS Bug Bounty Program. Through the process, the team also learns a lot about which ideas can be scaled up within the organisation. Instead of spending years and millions on developing a single solution that might fail upon delivery, 10x provides a channel for bottom-up pushes. They also help with the internal manoeuvring required to find legitimacy, the right timing, and find areas ripe for longer term structural changes within the organisation to scale up tested 10x solutions. The program is now in its second year.

What does adaptive innovation involve?

Adaptive innovation is essentially about a realisation that things are happening that don’t fit with what is expected. This might be about people reacting differently to a service than expected, and needing to adapt things in order to make it work. Or it might be about realising that there are new possibilities that could change how things are done, such as when social media arose and led to public services rethinking some of how they engaged with citizens. Adaptive innovation starts with the question “How might our evolved situation change how we do X?”

At a working level, adaptive innovation is about trying to learn more about how things really work. It is supported by methods and practices such as positive deviance, design, transparency, participatory or co-design, co-creation, exploration of edge cases, and through suggestions boxes and ideas management systems.

Examples of adaptive innovation that we have seen include:

- an online platform to support patients, caregivers and collaborators to come up with and share ideas, enabling those with health-related problems to find solutions to improve their and others’ quality of life

- an initiative to support a government department in adopting a user centred, end-to-end design approach to improving business priorities

- a tool for visualising and mapping flooding and disasters, as well as to assist with longer term climate change adaptation.

Adaptive innovation ranges from big to small in scope, and may be operational or relate to service-delivery or policy. The shared elements are that such innovations are about adapting to changed conditions or changed possibilities.

What to watch out for with adaptive innovation?

Adaptive innovation can occur where people experience a disconnect between what they are doing and what the world is telling them about what works, and they are curious as to why that is the case. Adaptive innovation involves a journey of discovery. There are some issues that can occur that are particular to this facet:

- Let a thousand flowers bloom. Adaptive innovation can generate a lot of different responses, which can allow for a lot of experimentation and testing of different approaches. This can be challenging to then incorporate back into standardised organisational or enterprise-wide approaches.

- Overly-responsive. The adaptation can be too thorough, leading to tailoring and customisation that may be entirely successful but is not warranted when seen from a wider perspective, or that may introduce difficulties to the wider workings of the system.

- Over-generalising. The lessons from one successful innovation may be seen as relevant for larger parts of the system when in reality there were specific contextual factors (capabilities, skills, particular actors) that were crucial and that may not be readily available in other settings (or at least, not without attention and cultivation).

- Competing tensions. The lessons from what works on the ground can sometimes be in tension with a more directed approach about what should be. “But this is what works” is not always a sufficient counter or response to “This is what we need to do”, as a more mission-oriented approach may have scale and reach or a longer time-frame for consideration.

How does adaptive innovation fit within a portfolio?

To be effective over the longer term, any organisation or system will require a portfolio approach in its investments and efforts. In an uncertain world, you cannot predict the type, scope or direction of change that you will be confronted with. Therefore governments need to invest in multiple strategies if they are to both avoid being blind-sided, and so that they have a range of choices available to them in how to respond.

So how does adaptive innovation fit within a portfolio approach?

Adaptive innovation is a vital part of the portfolio, as it is impossible for anyone within a system or an organisation to direct innovation in all of the places that it could or might need to occur. The central challenge with the adaptive innovation facet as part of a portfolio is holding in balance the ability for different actors to feel empowered and able to explore different possibilities and to adapt to their operating environment, and in ensuring that the innovation occurring does not lead to too much fragmentation or losing sight of key collective objectives.

What are the likely preconditions needed for adaptive innovation?

In order for adaptive innovation to occur, there are several preconditions that are necessary:

- Organisational slack or spare capacity. If there is no time or capacity to look at how things might be done differently, then adaptive innovation is unlikely to eventuate. Even if the idea is there, it will take some time and effort to explore how it might be implemented or to test and learn about how the world will respond.

- Autonomy or empowerment. If people do not feel empowered or able to try out new ideas, to explore different possibilities, or to test different ways of doing things then adaptive innovation will not occur.

How can adaptive innovation be supported?

What is helpful to adaptive innovation, rather than essential? We think there are some things that are especially relevant to supporting the facet of adaptive innovation:

- Socialising and diffusing innovative practices and the lessons associated with them, helping inspire and equip individuals with knowledge and ideas for how to innovate in their own contexts

- Celebrating innovative ideas and activities, to help demonstrate that innovation is welcomed, even when it is not directed or explicitly sought out

- Fostering and cultivation of feedback loops/engagement with citizens, to better strengthen the sense of where things need to change or where there is dissatisfaction with existing activity.

How to sustain adaptive innovation in the long-term?

To sustain adaptive innovation as a practice/portfolio component, it is valuable to consider:

- How feedback can be given where innovative ideas and initiatives from frontline staff or engaged partners are not taken up or embraced, so that the reasons are clear and people are not discouraged from putting forward new ideas or trying new things

- Providing clarity around what level of risk or what magnitude of experimentation is allowable without explicit authorisation or permission, so as to reduce the transaction costs involved with low-level testing and experimentation

- Foster informal and formal learning that helps staff and relevant actors keep on top of changes in practices, emerging opportunities, and shifts in expectations.

What can derail adaptive innovation?

Each facet is vulnerable to being jeopardised in different ways. Adaptive innovation can be disrupted or derailed by:

- Having very specific objectives or deliverables that preclude trying new things

- Processes that inhibit or limit engagement between the public service and others, so that opportunities for discovery and feedback become formulaic or occasional

- Placing those who have tried new things under significant scrutiny, so that others who may be inclined to explore new ideas feel apprehensive about trying.

What are the signs that the innovation activity is transitioning to another facet?

In our innovation facets model, we note that innovation activity can, over time, move from one to another. Some signs that adaptive innovation activity is transitioning to the other facets include:

- Towards enhancement-oriented innovation: Greater attention starts to be paid to the question of how thing are done and whether innovation can be used to improve that, rather than exploring new options or seeking further information about what works on the ground. At an individual project level, this may occur where a new idea or approach has been adopted, and there is a shift to focussing on how to make it work as well as possible. At a portfolio level, this may occur where there is a concern about consolidating existing changes, rather than experimenting with additional new options.

- Towards mission-oriented innovation: The focus on what is being learnt from the outside world takes second-order priority to the missions at hand, with more concern about shaping the changes occurring rather than responding to them. At an individual project level, this could happen as there is a shift to implementing new priorities or because the learning that has accompanied adaptive innovation has led to new insights about what needs to happen. At a portfolio level, the shift may be because there are pressing concerns (such as one or more crises or the commencement of a government with a very ambitious agenda) that necessitates a focus on core objectives.

- Towards anticipatory innovation: There is a shift from engaging with changing realities to thinking and exploring longer-term possibilities and what their implications are. This may occur at an individual project level when there may have been something learnt and tried that suggests an entirely new way of doing things, and changes the existing assumptions about what should be done. At a portfolio level, this might be when there is a focus on thinking about how people might react in tomorrow’s world, rather than today’s (e.g. there is a political significant event that reshapes everyone’s expectations about how things are going to play out).

An ongoing dialogue

The facets model has come out of our work with public servants from across different countries, and is a work in progress, with a number of hypotheses still to be fully tested.

Our aim is to help make practical sense of innovation for public servants, and so we value hearing from practitioners about their experiences and whether we’re hitting the right note. If you have any feedback, we welcome your comments, or you may wish to share your thoughts with us by email or on Twitter.

[1] Two of the definitions of adapt, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/adapt